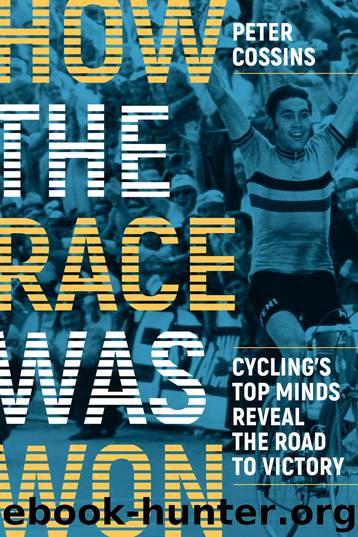

How the Race Was Won by Peter Cossins

Author:Peter Cossins

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: VeloPress

11

How to Win in the Mountains

Part of being a climber is that you can’t have a bad day and just draft in. If you are bad, you are gone. There’s no hiding.

Andy Hampsten

Sky is the new Saeco and climbing is the new sprinting. As bunch sprints become ever harder to control, the nearest the sport now gets to demonstrating a perfectly conceived lead-out is in the mountains, which says everything about the extent to which tactics have changed in this most challenging of racing terrains. With eight teammates lined out in front of him, Chris Froome has become the new Mario Cipollini, kept out of the wind until the moment he decides to accelerate, his rivals desperate to be on his wheel, hoping to be primed for the instant he attacks, their resources depleted by the battle to remain in Sky’s slipstream. This, cycling’s decision-makers would have you believe, is the contemporary reality of racing in the mountains. And their response to it? To cut one rider from every team from the start of the 2018 season to reduce control, to free up strategy and liberate the peloton’s born attackers, to return the sport to a more thrilling era of long-range attacks by solitary raiders and fluctuating fortunes in the high mountains. They hope to encourage the kind of tactical anarchy that fostered the exploits of Fausto Coppi, Federico Bahamontes, Eddy Merckx, and Marco Pantani, who were never hampered by such constraints.

However, if the concept of marginal gains tells us one thing, it is that Sky has essentially done no more than adapt or improve established practice to gain an advantage over their rivals. Nowhere is this more evident than in their strategic approach to racing in the mountains.

As with most advances that have taken place in racing during the postwar period, credit for instigating it goes to Coppi. As the peloton took on a more international and organized appearance in the early 1950s, the Italian realized that by maintaining a high tempo on climbs, he could keep pure climbers in check, neutering their sudden bursts of acceleration. Furthermore, by getting his teammates to infiltrate breakaways and attack off the front of the bunch, provoking a response from his rivals, he could sap their reserves to the extent that the mountains became a domain where he could dictate rather than defend.

What Coppi began, Jacques Anquetil continued. When climbers such as Federico Bahamontes and Raymond Poulidor jumped away from the French five-time Tour winner, he would reel them in in the same gradual manner that would be adopted later by Hinault, Miguel Indurain, and Sky domestiques in the service of Bradley Wiggins and Chris Froome.

Merckx had been initially dismissed as a Classics specialist whose strengths in that area would not translate to Grand Tour racing because he was regarded as not having the ability to contain the best climbers in the high mountains. However, he also embraced Coppi’s tactic to conquer his rivals in this terrain. He refined it, too, implementing his bullish and totally uncompromising strategy of la course en tête.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Born to Run: by Christopher McDougall(7125)

Bodyweight Strength Training Anatomy by Bret Contreras(4683)

Dynamic Alignment Through Imagery by Eric Franklin(4214)

Men's Health Best by Men's Health Magazine(2602)

The Coregasm Workout by Debby Herbenick(2272)

Starting Strength by Rippetoe Mark(2130)

Relentless by Tim S Grover(2084)

Endure by Alex Hutchinson(2026)

Core Performance Essentials by Mark Verstegen(2013)

Bigger Faster Stronger by Greg Shepard(1976)

Relentless by David Gething(1901)

Weight Training by Thomas Baechle(1774)

Runner's World Your Best Stride by Jonathan Beverly(1760)

Relentless: From Good to Great to Unstoppable by Tim S Grover(1699)

Practical Programming for Strength Training by Mark Rippetoe & Andy Baker(1618)

The Stretching Bible by Lexie Williamson(1587)

The Spartan Way by Joe De Sena(1574)

Good to Go by Christie Aschwanden(1480)

Dr. Jordan Metzl's Running Strong by Jordan Metzl(1410)